|

|

|

Discovery

Tour of Old Montréal’s

Archaeological Sites |

|

|

| Gaspard-Joseph

Chaussegros de Léry, born in Toulon in 1682,

was the King’s chief engineer in New France from

1716 to 1756. During this time, he planned and supervised

work on several defense systems in Montréal,

Québec City, Fort Chambly, Fort Niagara, Fort

Saint-Frédéric and Sault-Saint-Louis (Kahnawake).

Today, the spirit of Chaussegros de Léry beckons

us to discover these historic places by following these

marks on the ground, the archaeological reminders of

a bygone era. |

|

|

|

Did

You Know

That Montréal

Was a Fortified

City? |

|

|

Chaussegros de Léry

|

|

|

|

|

| When it was first founded,Montréal

was defended by fortified structures. As early as 1688, the colonial

administration urged its inhabitants to build a large number of

small forts,houses, fortified mills and redoubts—outworks

or fieldworks without flanking defences.The first stockade,made

of wood,was erected between 1687 and 1689. Louis XIV gave his

consent to build a stone fortification in 1712, and construction

began in 1716.

The new stone ramparts, built between 1717 and

1738, were a symbol of authority and a guarantee of security,

which both had a positive impact on the economy of Montréal.

In 1744, as war loomed, improvements were made. The ramparts were

designed according to the rules of fortification, the construction

art that takes the topography of the site into account. Since

Montréal is situated on relatively flat land, it was easy

to apply the principle of flanking, which requires that all parts

of the fortified wall be in the defenders’ full view.This

strategy was intended to protect the city from the greatest threat

to its security: a standard siege from a large military troop

pulling small artillery.

|

| Map of the City

of Montréal, September 10, 1725 by Chaussegros de Léry. Archives nationales (France), no 475B |

|

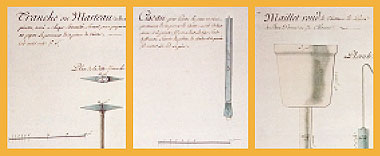

Tools

used for stonework. Anonymous,

circa 1740. Archives nationales du Québec

|

|

| A stonemasonry wall was

built on the side facing the St-Laurent River, where only attacks

by boat were possible. This wall was mounted with a parapet, pierced

with meurtrières, or gun sites, and, in some places,

was reinforced by a supporting wall and a terreplein, or sloping

bank.

A wall similar to the one facing the St-Laurent

was built on the land side to protect the enclosure from small

cannon fire.This wall was reinforced with a banquette—a

step running along the inside of the parapet and supporting the

wall-walk. A ditch and a glacis, or forward slope,were also planned

and together, they formed a defensive barrier over 25 metres wide.

Many types of craftsmen were recruited: the most

important were stonemasons and stonefitters, but haulers, carpenters,

blacksmiths, sawyers, locksmiths, roofers and other craftsmen

also lent their specialized skills to the site. However,most of

the workers were labourers, hired by building contractors and

construction supervisors to work alongside soldiers.

The 18th-century fortified city formed a dense

urban mosaic, dotted with large buildings—many belonging

to religious communities—landscaped with great walled gardens,

and nearly 400 houses were built during this time of expansion.

The fortifications were gradually dismantled between 1804 and

1817 following the adoption of The Act to Demolish the Old

Walls and Fortifications Surrounding the City of Montréal

in 1801.

Free from its enclosure walls, the city and its

suburbs now opened directly onto the river. This soon changed

the very pattern of the city, and as early as 1805, twice as many

people were living in the suburbs as in the city.

|

|

|